Traversing the Void

On finding identity through found objects and locating self in lineage.

Rhiannon

We’ve been talking about how your art practice is a form of placemaking, a sort of knowledge acquisition, a way to excavate, embody and explore ties to your Filipino roots.

Marisa

My work is really about lineage and ancestry as a form of making—how do I access ancestral knowledge as it relates to making, even though there’s a disconnect in the continuum. It’s as if there’s a “me” sort of jumping over this void in order to find it.

Rhiannon

What is that void?

Marisa

My parents moved from the Philippines to North America in the 1960s—the US funded the opening of many nursing schools in the Philippines to build a labour force and encouraged an influx of immigration at the time. My Dad went from Dapitan City first to New Jersey, my Mom from Baguio City to Toronto. They eventually met there, then moved to Ottawa, where I was born.

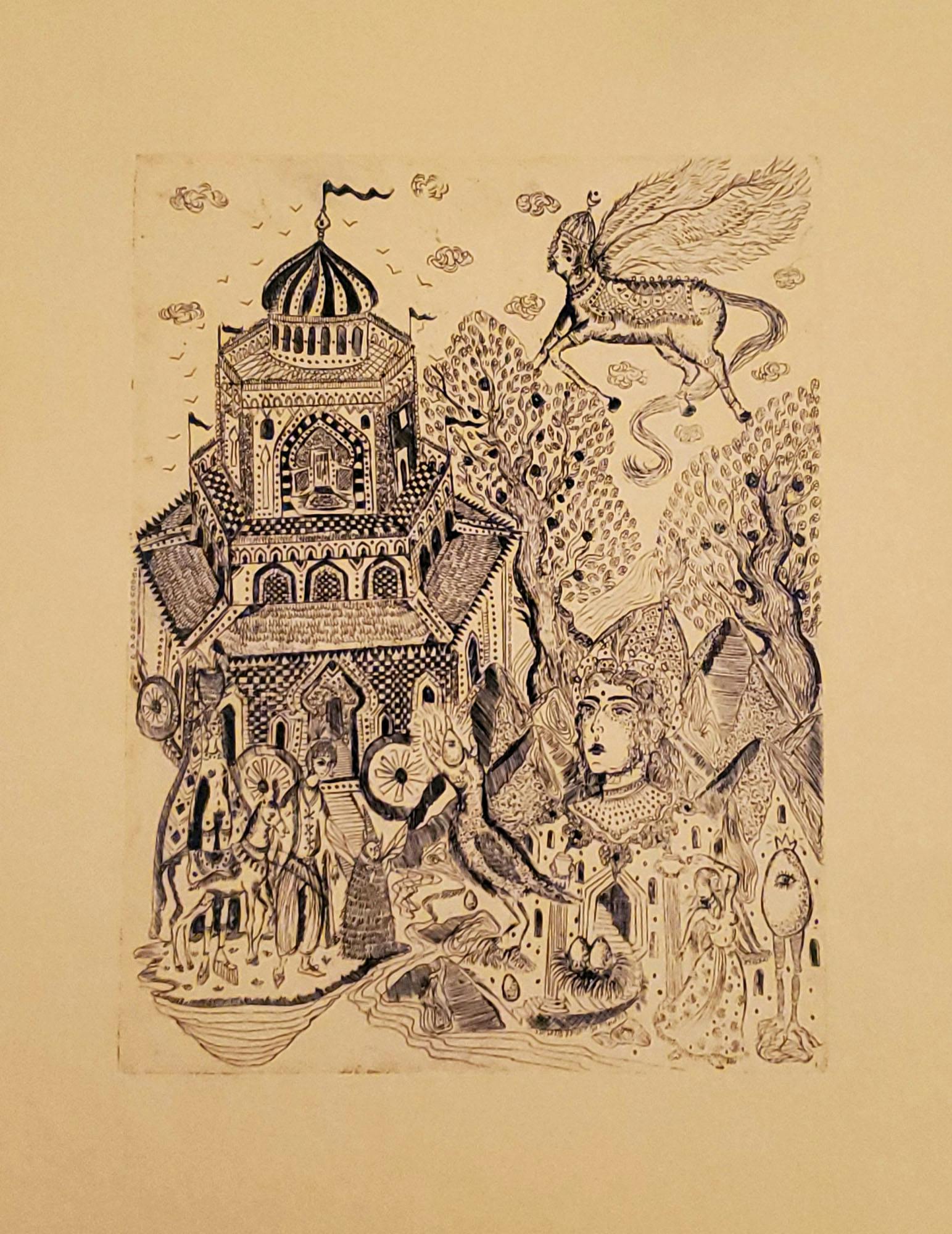

In much of my recent work, I’m thinking about locating myself in this cultural map of myself and my ancestors and my offspring and where I am, globally, historically. That space in between. A void, a lack, but also “an/other.”

I’ve been thinking about disorientation because that is a constant: disorientation here even though I am Canadian, and disorientation in the Philippines even though I have Filipino DNA; variations of the word “orient,”—both “orientation” and “Orient.”

Rhiannon

How do you work through those ideas in your art?

Marisa

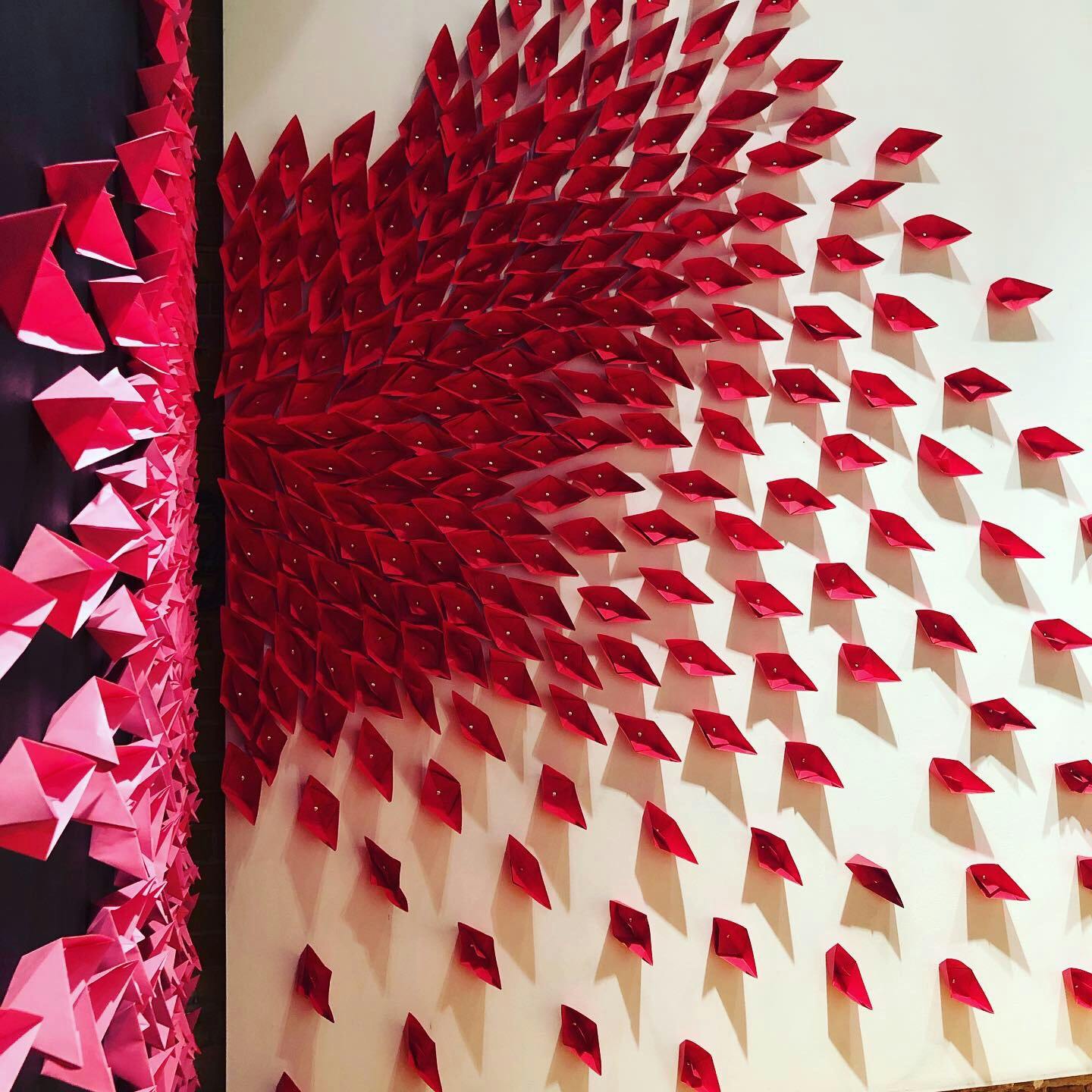

My materials are meaningful in that they always relate somehow to Filipino-ness. For example, pandan leaf, which is an indigenous plant; cardboard that references Balikbayan boxes; rubber that was a resource extracted during colonial occupation.

I do a lot of self-study about traditional making in the Philippines, specifically those that have to do with weaving, as well as the colonial linkages between the Philippines, North American and Europe. I’m becoming increasingly interested in notions of scarcity and value.

The essential nature of the material allows me to connect with my Filipino-ness even though I don’t have the tradition or the skills to express Filipino-ness in a traditional way. I still regard my identity as a Filipino in a very academic, studied way, because I’m learning it, I don’t feel like it’s mine necessarily. The Filipino-ness that appears in my work is a reflection of that, an admiration and attempt to create a visual language that is a hybrid of the level of identity that I have integrated so far.

Rhiannon

This integration is akin to weaving, isn’t it?

Marisa

For me, weaving is a technique and a metaphor. Physically I am bringing disparate materials together, but it’s also an emotional or psychic process of working through how to be.

There is no degree in how to ‘be’ in this kind of third space. It’s not academically recognized per se, it’s just this cultural growth, like spores. That spirit of third culture is a life force, whether it’s elegant or not, it is an evolutionary step.

Rhiannon

Marisa

It’s an imprint that happens. Not being born in the Philippines, there is a longing still, or a mourning still, for the country. It’s a place that I’ve never felt comfortable, in my own skin, so it’s like a ghost longing.

It also comes back to ideas of extraction or scarcity. The “valuable” things—resources, objects, people—all get sent away. There’s always an idea of caring for the Philippines, even if you weren’t born there, your existence here is for another person, another country. So how do I negotiate that? How do I ‘be’ here, in this constant state of ‘longing’?

Rhiannon

And your art is a place to work through that?

Marisa

My materials are meaningful in that they always relate somehow to Filipino-ness. For example, pandan leaf, which is an indigenous plant; cardboard that references Balikbayan boxes; rubber that was a resource extracted during colonial occupation.

I do a lot of self-study about traditional making in the Philippines, specifically those that have to do with weaving, as well as the colonial linkages between the Philippines, North American and Europe. I’m becoming increasingly interested in notions of scarcity and value.

The essential nature of the material allows me to connect with my Filipino-ness even though I don’t have the tradition or the skills to express Filipino-ness in a traditional way. I still regard my identity as a Filipino in a very academic, studied way, because I’m learning it, I don’t feel like it’s mine necessarily. The Filipino-ness that appears in my work is a reflection of that, an admiration and attempt to create a visual language that is a hybrid of the level of identity that I have integrated so far.

Rhiannon

This integration is akin to weaving, isn’t it?

Marisa

For me, weaving is a technique and a metaphor. Physically I am bringing disparate materials together, but it’s also an emotional or psychic process of working through how to be.

There is no degree in how to ‘be’ in this kind of third space. It’s not academically recognized per se, it’s just this cultural growth, like spores. That spirit of third culture is a life force, whether it’s elegant or not, it is an evolutionary step.

Rhiannon

Marisa

It’s an imprint that happens. Not being born in the Philippines, there is a longing still, or a mourning still, for the country. It’s a place that I’ve never felt comfortable, in my own skin, so it’s like a ghost longing.

It also comes back to ideas of extraction or scarcity. The “valuable” things—resources, objects, people—all get sent away. There’s always an idea of caring for the Philippines, even if you weren’t born there, your existence here is for another person, another country. So how do I negotiate that? How do I ‘be’ here, in this constant state of ‘longing’?

Rhiannon

And your art is a place to work through that?

Marisa

Yes. Increasingly so during the pandemic.

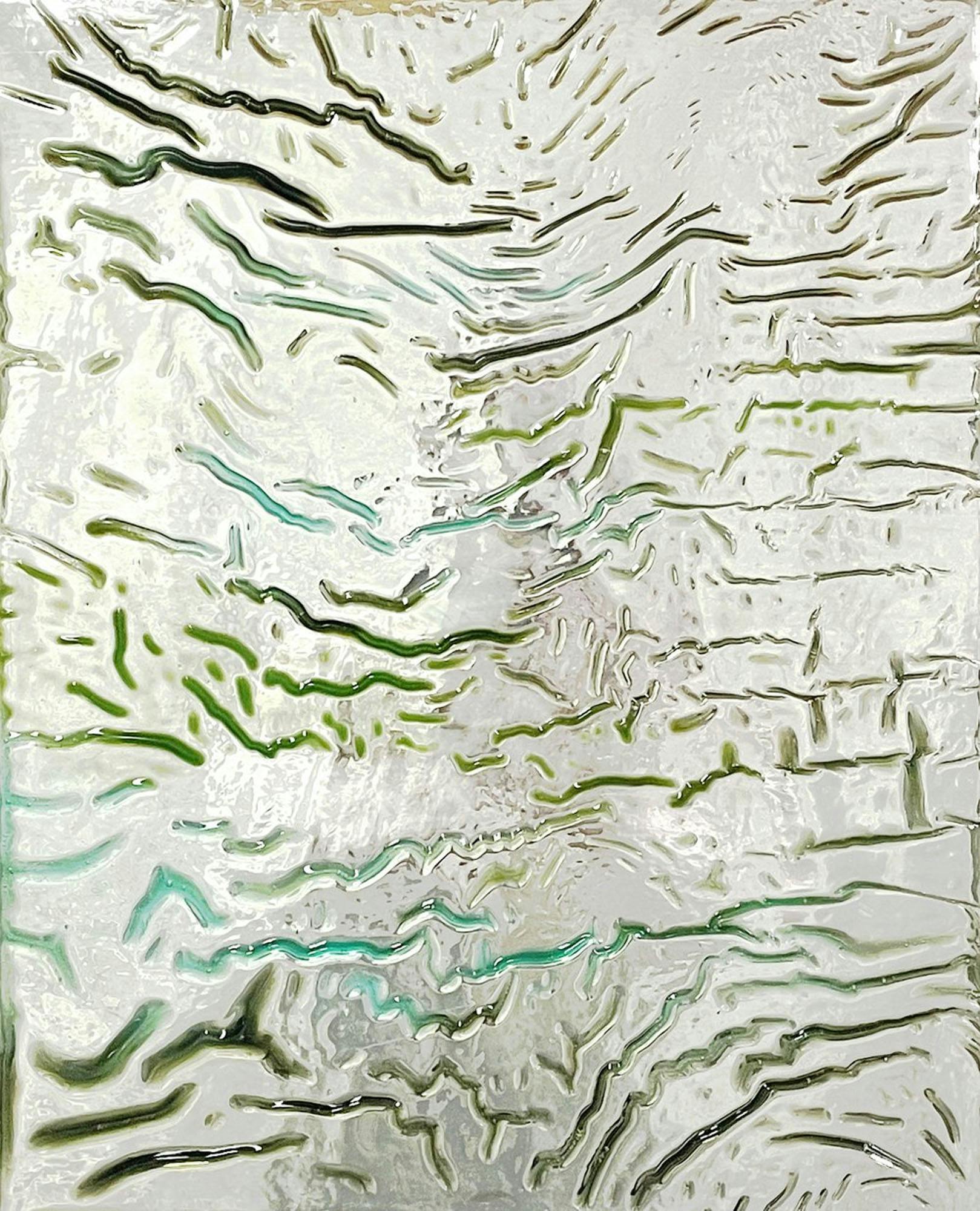

During the first lockdowns, I was making work for a show that was ultimately delayed, and I got to really spend time, and live with, the pieces I was making. They went from being visual objects to actual entities, “beings” that I was caring for, or that were even caring for me.

One work, Pundasyon, 2021 I had in my kitchen for months and months, I walked over it every day. I worked on it, I cooked on it, it became so important—I was creating it, and it was also giving back a source of stability. How do I create, and be held by something stable. A place to land, you know.

Rhiannon

Marisa