Detroit is just under a four hour drive from Nep Sidhu’s hometown of Toronto. There is a musical continuum that resides along that geographical pathway that Sidhu has engaged for over twenty years as a function of his love for music and specifically the collaborative engagement that is inherent to the genre known as techno. On the occasion of his first solo exhibition in the United States, the multidisciplinary, Toronto-based artist chose the city of Detroit to continue his 10 plus year investigations into the architecture of divine formlessness and sonic potentialities as manifested through sound, poetry, textile, sculpture, and glyph. Paradox of Harmonics could have only happened in Detroit, a city that has consistently birthed and sustained internationally renowned musicians and entertainers.

Detroit is most well known for being the birthplace of Motown’s first African-American music label, which was located in Detroit between 1959 and 1972. Detroit remained fertile ground for Black music and by the 1980s, with the emergence of the genre known as techno, groups such as The Belleville Three and Cybotron, and DJs like The Wizard (Jeff Mills), Mike Huckaby and his brother Craig Huckaby, and later Theo Parrish, and Waajeed, just to name a few, solidified and further leveraged the profile of the city nationally and internationally as a site for prolific and innovative music making.

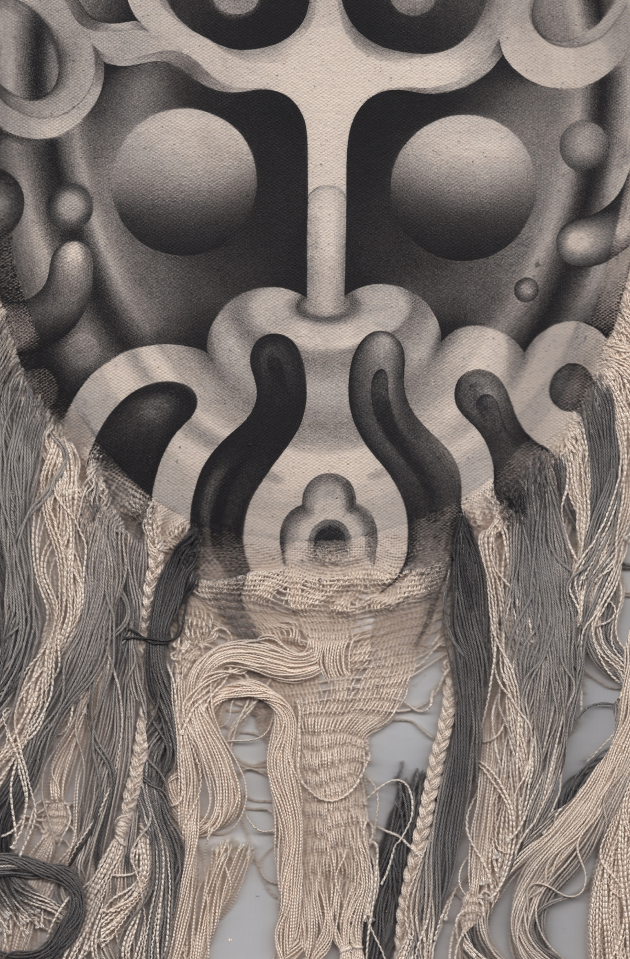

In this exhibition, Sidhu functions in multiple roles of which artist is but one. There is the architect who manipulates sundry materials to fashion vessels which simultaneously both house and represent various iterations of the divine. Three of these vessels comprise the Omniverse 7000 and Disappearance Potential, that together form a triptych sound system built to hold, care for, and emit various melodies and harmonies that permeate the exhibition space, restoring time to its cyclical origins, and permeate the spatial and corporeal realities in its midst. The construction of this sound system is a collusion of roles including that of audio engineer, metal fabricator, ‘selecta’, and collaborator. It brings together various founts of knowledge—ancient and contemporary—with the goal of elevating sound to such a climax that those experiencing it enter a state of profound ecstasy.

Selecta/selector is a term that emerged out of Jamaican reggae sound system culture, originally purported to have referred to the individual who selected the records that the DJ would then play. In recent years, however, it has become synonymous with a person who both selects and plays the records. I find this to still be an incomplete understanding, and for the sake of this article, the term should be understood as a person who has an intensely profound knowledge of music that is often shared with other selectas and a music loving community that co-signs that knowledge through the reciprocity of dance. Selectas often refuse the title of DJ, or any title at all and may simply say, “I just play records.”

‘Paradox of Harmonics’

MOCAD

‘Paradox of Harmonics’

MOCAD

Sidhu’s role as collaborator is among the most grounding and sentient forces within this exhibition. It is in this role that we can envision and better understand his foundation as a practitioner of Sikhi. Of the many ideals that Sikhi requires its adherents to embody, the most fundamental is to be a student. In fact, that is the definition of the word Sikh. Understanding Sidhu as a Sikh—as a student—becomes crucial to any reading of this exhibition, in particular its collaborative underpinnings.

As a student, there is consistent acknowledgement that there is someone or something that knows more than you and who is in position to support and advance your learning. The most fruitful collaborations occur when individuals coalesce with an understanding and acknowledgement that the group can provide a level of advancement that is unlikely, if not impossible, individually. To that end, Sidhu has united an indomitable group of co-conspirators who lent their skill, thought, experience, and talent to this exhibition. These include video artist and audio instrument designer Phil Baljeu, musician Kahil El’Zabar, maker and educator Craig Huckaby, multimedia artist Rajni Perera, and sound artist and audio instrument designer Devon Turnbull.

…Or better still, teleport the whole planet here through music.

-Sun Ra

Sonically and aesthetically Sidhu has consistently engaged the work of Sun Ra. Sun Ra is most well known for his musical contribution; however, his discursive contributions to deeper understandings of the generative possibilities of space travel and the centrality of music to that endeavour, build on the theology and origin stories of myriad African peoples, the legacies of which are still present and practiced contemporarily on the African continent and in it’s diaspora.

One reading of Sun Ra, the one that Sidhu engages, understands him as in conversation with the divine, a conversation that reshaped the course of his life. In John F. Szwed’s 1997 book Space is the Place: The Lives and Times of Sun Ra, Szwed shares Sun Ra’s details of this encounter,

“My whole body changed into something else. I could see through myself. And I went up… I wasn’t in human form… I landed on a planet that I identified as Saturn… they teleported me and I was down on [a] stage with them. They wanted to talk with me. They had one little antenna on each ear. A little antenna over each eye. They talked to me. They told me to stop [attending college] because there was going to be great trouble in schools… the world was going into complete chaos… I would speak [through music], and the world would listen. That’s what they told me.”

Sidhu has united an indomitable group of co-conspirators

Sun Ra speaks of this experience in terms akin to space exploration, and given the date he ascribes to this revelation, he would certainly have been decades ahead of all documented human accomplishments where space travel is concerned. Zooming out, the meaning of Sun Ra’s account points to the paradoxical power of music. Beyond something to just enjoy, a unidirectional reception of entertainment from musician to listener, it is an energy that can propel one into previously unknown geographies, other worlds (space), a new consciousness, and a liberated state of being. It is as Sun Ra states in Space is the Place,

“I’m not real, I’m just like you. You don’t exist in this society. If you did, your people wouldn’t be seeking equal rights. You’re not real, if you were you’d have some status among the nations of the world. So we are both myths. I do not come to you as a reality, I come to you as the myth because that is what black people are: myths. I came from a dream that the black man dreamed long ago. I’m actually a presence sent to you by your ancestors.”

It is an energy that can propel one into previously unknown geographies

Of the more subtle threads uplifting this exhibition is the reference to the Divine. Sidhu speaks of the Divine as analogous to Mother Nature as shared in his narrative poem accompanying the work “An Immeasurable Melody”. It is simultaneously a salute to Guru Gobind Singh Ji, who in the Sikh holy text called the Dasam Granth, devotes at least three sections to the celebration of the feminine in the form of the goddess Durga. It is also a salute to Sikhi’s founder Guru Nanak Dev Ji, who, upon founding Sikhi denounced the caste system, and when asked about the status of women responded, “How can she be considered inferior when she gives birth to kings?”

This devotion to and elevation of women and the feminine is not lost on Sidhu. In 2005, his family established (and still maintains) a boxing school in the Chakhar community in the Panjab, which was founded to focus on the challenges unique to young women in that community. More personally, Sidhu lost his own mother several years ago. If we trust in the paradoxical nature of both Sidhu’s and Sun Ra’s harmonics, we know that in these works she is present. In every thread, beat, angle, paint stroke, and breath. She is there.

We play the drum until the wound begins to show signs of healing

On April 23, 2022 there was a public program moderated by Jova Lynne, the Susanne Feld Senior Curator at MOCAD with special guests Kahil El Zabar and Craig Huckaby. I recall Huckaby opening his commentary by sharing that he never imagined a world without his brother Mike Huckaby, who passed in 2020. Following this, Sidhu shared he too had lost his brother and mother, and that pushing forward with his practice subsequent to their deaths, while immeasurably challenging, served as a very necessary salve that continued to keep them alive in the now.

This moving exchange spurred within me numerous rapid fire thoughts about the deaths I have personally suffered, those I have observed loved one’s suffer, and the ways we mourn communally. I recalled the theologies and philosophies I adhere to and our protocols for resolving suffering. We delimit space and consecrate it, we invite the family and the community of the suffering individuals, and we play the drum until the wound begins to show signs of healing.

One question remained with me in that moment: with what do we fill our wounds so that they may begin to heal?

The answer: Harmonics.