Rust as Memory, but also as Time

On giants, memory, embodiment and the encroaching death of capitalism

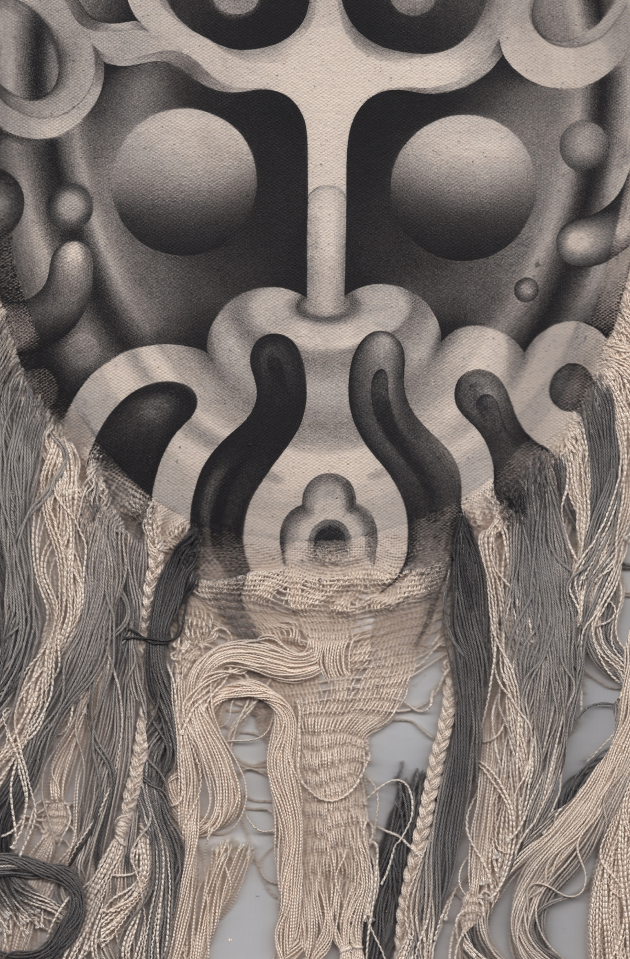

The trees weep, the mountain still, the bodies rust features a new body of work by Derek Liddington in which the genre of landscape is the central focus. Having turned away from performance and drawing in recent years to explore the medium of painting, Liddington examines how we experience the landscape rather than how we see it. He challenges the material limitations of the canvas with strategies that seek to capture transformation and movement. By doing so, he confronts the historical canon of painting as a way to reconsider its legacy.

– Anne-Marie St-Jean Aubre, Musée d’art de Joliette

Meghan

I’m curious about the role of memory. Time has been so amorphous, especially in the past couple of years. You’ve spoken of memory in your past work. What does memory mean to you? And to this work?

Derek

This body of work comes from a series of works from four years ago, that were all based on memories. I wanted to think about how memory differs from documentation. Lived memory and as different from learned memories. How we learn histories and how they play into how we make, how we are, and how we engage. It felt like a transition for me. I had been thinking about my own experience, and how it speaks to the way I see visual images, or the way I see perspective. This show was a fusion of those two things. This relationship of memory is a necessity for lived experience. This show is thinking about time and memory, subject and memory.

Meghan

That’s interesting. In the past couple of years, I’ve been exploring the embodied dimension of memory. My memories live like cracked tissues and achy collarbones and the sound of snow or, or air. Is there something that sticks out as being strongly felt, or embodied from creating this exhibition?

One could see rust as a memory of time on metal. But also, a blemish.

Derek

I really love that. Thinking of memory as your body having these marks, and shifts, and changes. In the show, many of the titles allude to this idea of rust. One could see rust as a memory of time on metal. But also, a blemish. I was trying to correlate the relationship between body and landscape. Thinking about the time of a tree, the time of rocks, the time of minerals, and then how we fit within that. Memory like the rings of a tree. Tissues stretching and retracting. There’s something about the way we process time that I’m really interested in. That’s perhaps one of the things that abstraction offers. In abstracting, we assume there’s a reduction of information, but it also offers potential. When something is reduced, we can project onto what it is. A lot of these paintings were: how do I paint time? How do I paint memory? How do I paint a blemish that feels like rust, that also feels like it’s flat, but also feels like it has surface and depth.

Meghan

Memory living within a tree or a nonhuman entity. Bodies and rust. What were the challenges in addressing both human and nonhuman ontologies in this work? In negotiating relationships with bodies, but also with landscape?

There was no way to get enough perspective to understand that it is a dying corpse.

Derek

This started as a show on bodies and movement. At first, I did a series of investigations on the movement of my grandfather. I felt way too close to that subject. I was unable to separate enough from my grandfather, or the memory of him. The work felt distant. But what stemmed from this, was this thinking through body and landscape. From here, the show shifted.

I read about giants. My interest in giants came from this lecture that I listened to about economic systems and the fall of capitalism. It suggested that—and I love this metaphor—that capitalism was a giant, and that the giant was dying, but we couldn’t see it dying because it was so large. The components that we did see, didn’t seem like the giant, it didn’t seem like capitalism. There was no way to get enough perspective to understand that it is a dying corpse.

I started researching the history of giants. Giants are humanoid bodies, usually non gendered, that exist in space. We can’t see them because they’re so large. We can’t ever get perspective to see them. That was a beautiful transition–trying to scale ourselves up to understand the natural world. Giants were used to understand earthquakes. Giants were used to describe both human and natural moments that we couldn’t quite comprehend. And so for me, I couldn’t comprehend our bodies and landscape, so it felt natural to bring the giant in as this system. All the works in the show have bodies that are exploded in a way that are made larger than a human body could be. From there, it’s a way of negotiating the landscape. It becomes so big we can see into it.

Meghan

That’s fascinating for me. I’m working on a character right now. Mélisande from Debussy’s Pelléas and Mélisande. She’s found within a forest too large for the audience to comprehend. It encompasses her. When I interpret her, I imagine my body being engulfed by a forest. Did you imagine how your audience would experience these works? Did you imagine what they would sense, or feel?

How do I create something that feels like it's moving? How do I play with perspective?

Derek

A lot of my painting speaks to the viewership and perspective. How do I create something that feels like it’s moving? How do I play with perspective? When I was installing this show, I was thinking about how the works related to space. The painted walls allow the paintings to extend to the space, creating a spatial relationship of the gallery. Scale shifted, not just within the painting. The thought was that when one moved around it, they could discover ideas of scale and perspective from a felt space.

I have a huge interest in theater and the idea of prop and stage. The illusion of the stage. So much of my past work had to do with theatrical constructs of stage, so when I have the ability to play with space, I try to do that.

Meghan

I’m so curious about this idea of immersion. You’ve created a space in which the audience can be immersed, but in the process, you were immersed in the act of painting—a new and different practice for you. What did it feel like to immerse yourself in this practice, in your body, to create this, knowing the complementary but different practices in your prior work?

You have to fill in the missing, undigested elements. This created a necessary distance.

Derek

I’m comfortable in performance. My comfort was and is, to be in space in my body. Literally, performing. I have been pushing back on that over the last ten years of my practice. Now, I’ve removed the visibility of my body from the work. I want to be out of it. Going into this show, I knew that I didn’t want it to be about my body or my biography. This was a challenge because a lot of my thinking on the idea of time is through my relationship to myself, my own body, my son, my father, my family, the land.

So, to pull myself out of a painting, I came to painting from memory. When you’re painting from memory, there is a disconnect. You have to fill in the missing, undigested elements. This created a necessary distance. The embodiment was in the distance found through memory. I was trying to disconnect myself if I felt too close. Maybe embodiment is when something feels right? But is that reflective of expectation? Maybe as an artist, knowing the visceral but striving for something unsettled. I think that is a form of embodiment. Maybe.