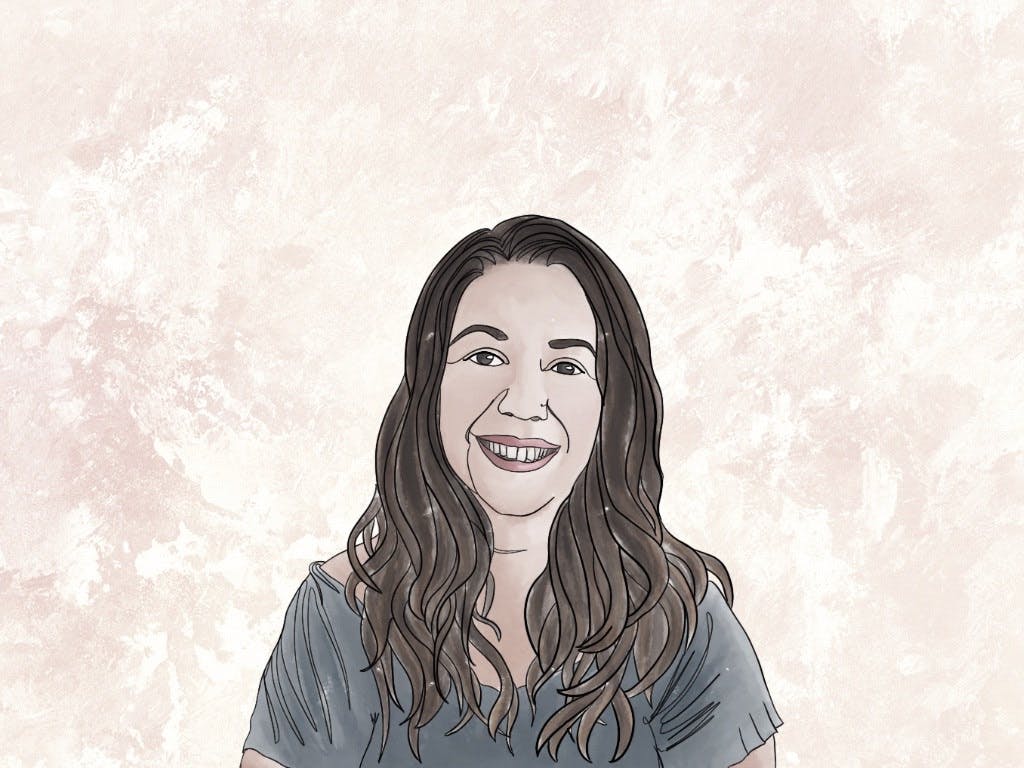

Navigating queer identity can be a daunting task in Iran, despite conditional acceptance of trans identity and the inherent gender neutrality of the farsi language. Iranian-American Harvard academic Afasaneh Najmabadi has a veritable oeuvre dedicated to the documentation of gender and sexuality in the country, both past and present, however it’s the former that caught the eye of Tehrani artist Mahsa Merci. Recently relocated to Toronto after completing an MFA at the University of Manitoba, Merci has been grappling with gender, sexual identity and the body from the earliest days of her art practice. The reasons for this were initially unknown to the artist, who revels in allowing her subconscious to lead her practice, before realizing at 28 years of age that she identified as queer.

It’s this personal journey that is strongly reflected in Merci’s recent exhibition Silent Stars, a hypnotic celebration of her own psychic impulses and an enthusiastic embrace of the queer community at large. Academic texts are often a strong source for Merci’s inspiration; and while Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble played a role, Merci recounts Najmabadi’s seminal work on gender and sexulity in pre-modern Iran, Women with Mustaches, and Men Without Beards, as a major influence. Through literary texts and paintings from pre-modern Persia, Najmabadi notes the commonplace occurrence of same-sex intimate relationships, and the difficulty in determining the gender of the young subjects frequently featured in these historical artworks. In the artist’s own words: “When you see so many paintings from that century in Iran you cannot tell which character is male or female. Little shape of the hat or clothes, but that’s it. Face, eyebrows, hair, clothes, gestures; there’s no difference between male and female in the paintings.”

When I went to these places and tried to find my face, my whole face, I couldn’t. It was shattered into a thousand pieces

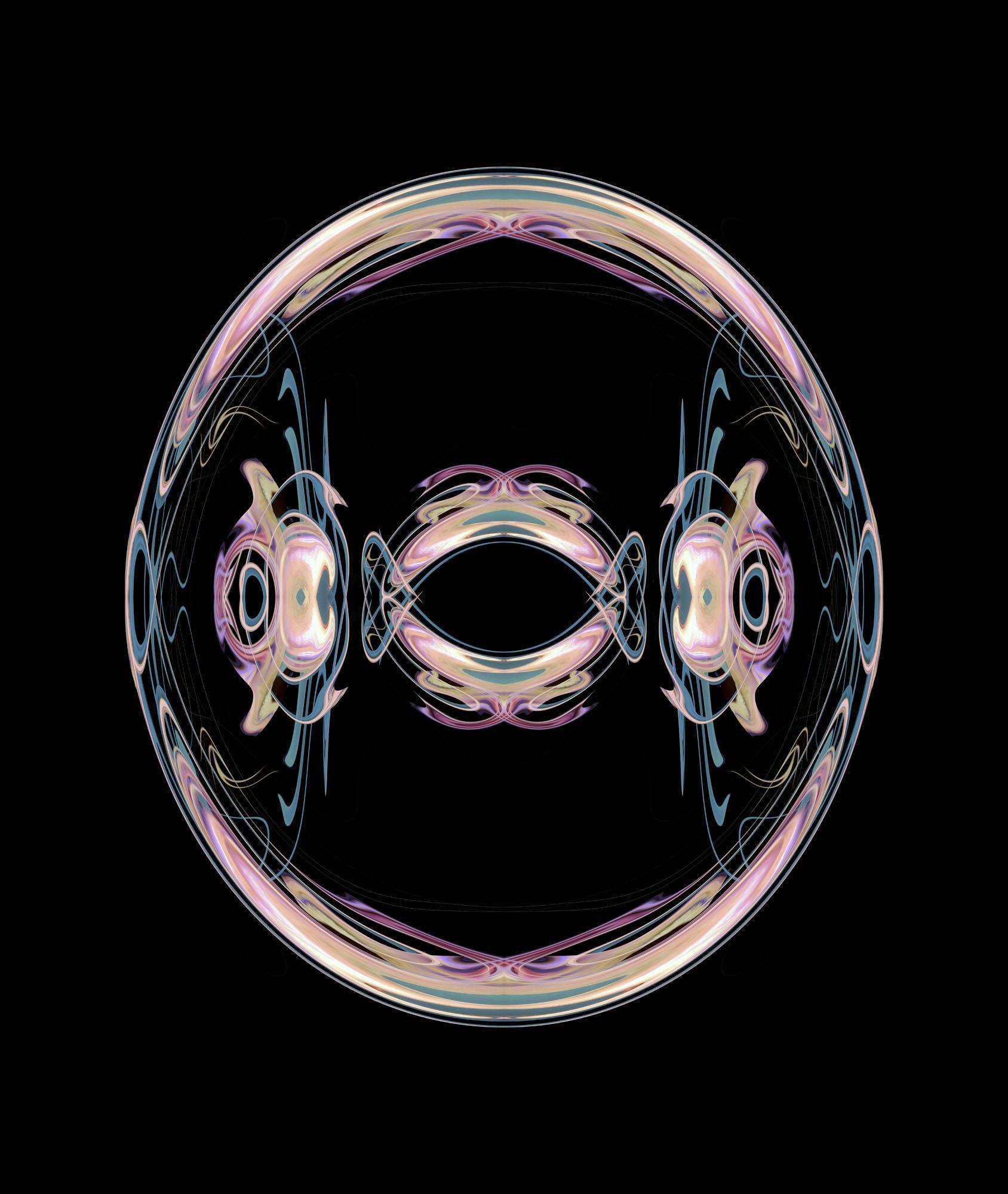

Referencing the triptych near the exhibit entrance, Merci cites these pieces as the most directly inspired by Najmabadi’s text. Featuring a blend of traditional mirror craft technique, a nod to “old Islamic architecture” in shape and style, the artist also adds a playful and intriguing touch—hundreds of individual false eyelashes meticulously placed at the frames edges, creating a hirsute border surrounding this self-proclaimed memorial to their culture and other queer Iranian people. The strategically arranged mirrors in this context also act as a metaphor of censorship for Merci. “On TV when they want to censor a person, the portrait is pixelated. When you want to see your face in these mirrors you become pixelated…As a queer Iranian, our identities are denied, but that is not my culture, we always existed in the history.”

Mirrors are abundant in Merci’s work, and while my reflexive reaction was towards disco balls (particulary as a homage to the world of nightlife as a creative bastion for alternative lifestyles, queer and otherwise), her usage is more closely connected to the time-honoured craft technique known as āʾīna-kārī. Seen in multiple religious and historical sites in Iran, this tradition became popularized during the Zand and Qajar periods for interior decor in both public and private spaces. Contemporary artists engaging with āʾīna-kārī began in the 1950s with Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, whose practice spoke to the symbolic representation in Islamic geometry and Sufism, and more recently Timo Nasseri’s exploration of the aniconic nature of the aforementioned. The spiritual essence of losing oneself in fractured reflection in search of a higher plane is not lost on Merci. Recalling her childhood visiting some of these religious and historical sites, the experience was formative and intense. “When I went to these places and tried to find my face, my whole face, I couldn’t. It was shattered into a thousand pieces. I tried to play with the mirrors, move my head in different ways to find myself—I get goosebumps when I talk about that. It’s a feeling I’ve always kept, my subconscious keeps it, this feeling of ‘just find yourself’.”

When I went to these places and tried to find my face, my whole face, I couldn’t. It was shattered into a thousand pieces

Mirrors are abundant in Merci’s work, and while my reflexive reaction was towards disco balls (particulary as a homage to the world of nightlife as a creative bastion for alternative lifestyles, queer and otherwise), her usage is more closely connected to the time-honoured craft technique known as āʾīna-kārī. Seen in multiple religious and historical sites in Iran, this tradition became popularized during the Zand and Qajar periods for interior decor in both public and private spaces. Contemporary artists engaging with āʾīna-kārī began in the 1950s with Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, whose practice spoke to the symbolic representation in Islamic geometry and Sufism, and more recently Timo Nasseri’s exploration of the aniconic nature of the aforementioned. The spiritual essence of losing oneself in fractured reflection in search of a higher plane is not lost on Merci. Recalling her childhood visiting some of these religious and historical sites, the experience was formative and intense. “When I went to these places and tried to find my face, my whole face, I couldn’t. It was shattered into a thousand pieces. I tried to play with the mirrors, move my head in different ways to find myself—I get goosebumps when I talk about that. It’s a feeling I’ve always kept, my subconscious keeps it, this feeling of ‘just find yourself’.”

There is usually a strong gender divide; women participate, while men prefer not to touch

Highlighted by Najmabadi, the role of mirrors in Qajar art suggestively asserts the viewer to assume a participatory role. As the figures in the paintings from this period possess strong outward gazes, mirrors in the image are positioned such that they implicate the viewer, inviting them to be “an accomplice in the pleasures…engaged in the production and circulation of desire inside and outside of the visual text.” Merci takes this notion a step further, encouraging viewers to touch her work. This stems in part from her own inclinations to do the same in the gallery space, but also her desire that they sense her presence in the object; connect to the essence of her soul she’s imbued in the piece. She’s also intrigued by which viewers accept this invitation and which ones don’t, noting there is usually a strong gender divide; women participate, while men prefer not to touch, even when given permission to do so.

The presumed dichotomy of natural vs unnatural/artificial is questioned and agitated in a liminal, otherworldly space

Each medium provides a different experience for Merci—her textural painting style, one of her earlier techniques, is the form she feels most comfortable in reproducing, and represents her conscious self. Citing the documentary style of Nan Goldin as an influence, painting is where she’s able to chronicle the queer community, whether it be people from her personal life or those she finds via social media. Animation, as seen on display in the exhibit’s video installation, “Limbo,”allows her to create atmospheres and environments unavailable to her in other mediums. Central to her work is the disassembling of false binaries; the presumed dichotomy of natural vs unnatural/artificial is questioned and agitated in a liminal, otherworldly space. A disembodied head appearing in varied simulated environs, represents her own psychological journey, as well as the physical one she takes as an immigrant.

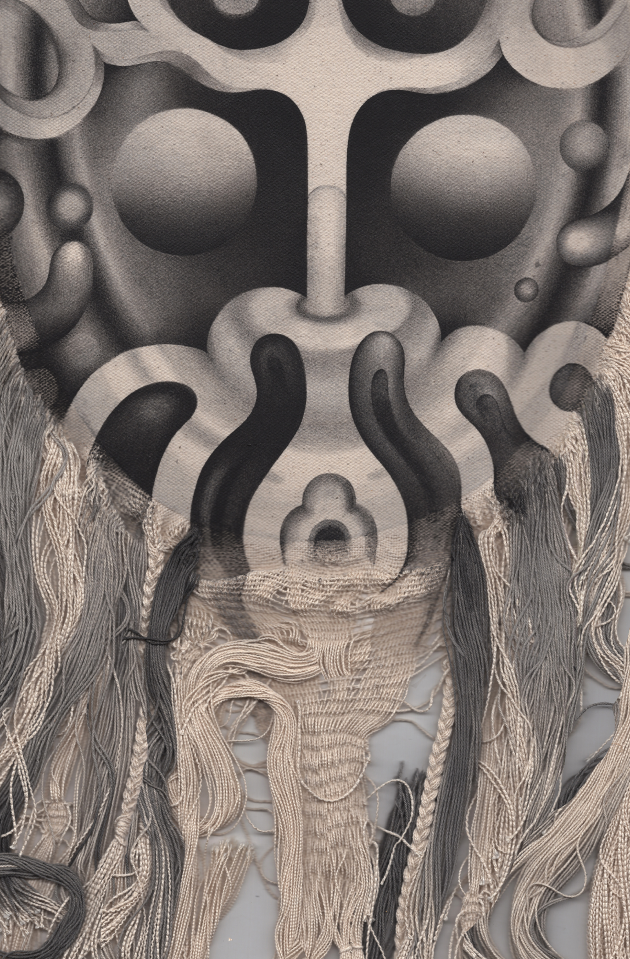

Sculpture is where she is at her most experimental—a place to play

If painting and animation are more assured mediums for Merci at this stage of her career, sculpture is where she is at her most experimental—a place to play. Visibly influenced by David Altmejd’s surrealist fusion of the seductive and the macabre, she breaks apart and reforms the body, using a breathtaking array of elements. Unleashing herself into a heady mix of fantasy, masque and kitsch, Merci transforms readily accessible materials, bedazzling mannequin heads and torsos, adding technicolour wigs, brightly coloured nails, fishnet stockings, and false eyelashes to dizzying effect. One of her more personal pieces is a disembodied head mounted on a plastic column, blinded by the words “SOMETHING IS MISSING.” This is a nod to her earlier work, when she focused on sexuality and genitalia, consciously unaware of her body’s deeper knowing.

She believes the buried catalyst will be revealed at a later time, long after the work is complete

Having lived so much of her life in the dark, due to the exclusion of queer voices when she was growing up, Merci describes this existence as one of “depression, stress, and trauma.” It’s no wonder she has an abiding interest in the field of psychology, and has more recently engaged with the work of psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan. When asked about the recurrent act of deconstructing and reconstituting the body in her work, Merci confesses she hasn’t found the answer yet. She believes the buried catalyst will be revealed at a later time, long after the work is complete. Perhaps it is fitting, as an embodiment of Lacan’s theory of jouissance, she continues on this journey into the unknown, as a willing channel of the abundant chaotic stream that is her sub/consciousness.